On January 27th of this year, 14-year-old Emily Pike, a member of the San Carlos Apache tribe, set out alone from her group home in Mesa, Arizona. She never returned. A few weeks later, on February 14th, her dismembered body was discovered some miles away, prompting an outpouring of sorrow and demands for justice from her family and community as well Indigenous communities across the country.

I didn’t hear about any of this until I saw her name written on a tee-shirt while shopping for something else. The death of an Indigenous girl in the United States, even so horrific a death, is hardly newsworthy. It happens all the time.

A 2016 study by the National Institute for Justice reported that 84.3% of Indigenous women in America (including Alaska) have experienced violence in their lifetimes. 56.1% have experienced sexual violence.1 The CDC reported in 2020 that murder is the third highest cause of death for Indigenous women aged 10-24 (5th highest for Indigenous women aged 25-34, and still in the top ten up to age 45). On some reservations in the US, Indigenous women are being murdered at a rate of more than 10 times the national average. An article published in the Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, titled: “A Modern Trail of Tears: The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) Crisis in America,” also noted that: “those of indigenous ethnicity are 2.5 times as likely to experience violent crime and at least 2 times more likely to experience rape or sexual assault crimes than people of other races in the United States.”2 The vast majority of this violence is perpetrated by white male offenders.

And these are the cases that are correctly reported.

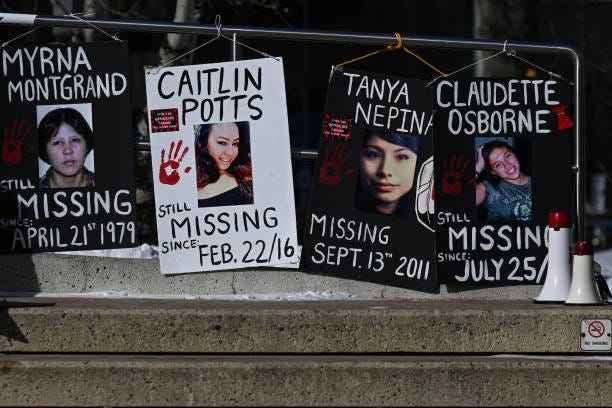

The National Crime Information Center (NCIC) reported that, as of 2016, 5,712 Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirits (non-binary and trans people) have been reported missing in the United States. Of those, only 116 cases have been logged into the Department of Justice’s Missing Person’s database.3 The CDC states that it is projected that less than half of all sexual crimes committed are ever reported. Unidentified remains of Indigenous women are 250% more likely to remain unidentified; and, according to a report by the Urban Indian Health Institute, are often mistakenly classified as Latina or Asian-America.4 The UIHI hauntingly declares that MMIWG+ (Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirits) disappear three times: first in life, then in the media, and finally from the data. Like they never existed at all.

I have read a lot of disturbing statistics over the years, but nothing effected me as physically as this has. My eyes froze on the “third leading cause of death” statistic. I thought I might vomit. Anguish is the only word that could describe what I was feeling as I sat, both hands clamped over my mouth while the tears poured. I can only imagine what it would feel like to be personally affected by those numbers. As a mother of two daughters, how would it feel to know that my girls probably have a better chance of returned unscathed from multiple military tours of duty in a war zone than they would from simply being born Indigenous? I can’t wrap my head around numbers like these, let alone the fact that I’ve never heard them before. But why would I have? The problem is institutionalized, and it began long, long before Emily Pike was born.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to CrossWitch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.